The telephone, a seemingly simple device that has connected the world for over a century, is a marvel of applied physics and electrical engineering. While we now carry miniature supercomputers in our pockets that can perform a thousand functions, the fundamental principle behind a traditional telephone remains a fascinating study of how we translate a complex physical phenomenon—the human voice—into an electrical signal and back again. This article delves into the scientific points of its working, exploring the ingenious components, the underlying principles, and some lesser-known facts that shaped its evolution.

The Core Principle: A Tale of Transduction

At its heart, a telephone is a transducer. Transduction is the process of converting energy from one form to another. A traditional telephone performs this function in two crucial steps:

* Transmitting: It converts sound energy (the vibrations of your voice) into electrical energy.

* Receiving: It converts that electrical energy back into sound energy.

This seemingly magical process is executed by two key components in the telephone’s handset: the transmitter (also known as the microphone) and the receiver (the speaker).

The Transmitter: A Journey from Carbon to Clarity

The most significant technological leap in the early telephone was the development of a reliable transmitter. Alexander Graham Bell’s original device, the “liquid transmitter,” was a crude and inefficient prototype. The true revolution came with the invention of the carbon microphone by Thomas Edison in 1878. This invention made the telephone a commercially viable product and was the standard for over a century.

How it Works (The Carbon Microphone):

The carbon microphone is a brilliant application of variable resistance. Inside the mouthpiece of the telephone, there is a small chamber filled with tiny granules of carbon (often graphite). This chamber is sandwiched between two metal plates, one of which is a thin, flexible diaphragm.

* Sound Waves Arrive: When a person speaks into the mouthpiece, the sound waves from their voice cause the diaphragm to vibrate.

* Pressure Changes: These vibrations compress and decompress the carbon granules inside the chamber.

* Variable Resistance: As the granules are compressed, they are pushed closer together, which lowers their electrical resistance. When the granules decompress, they move apart, increasing their resistance.

* Modulating the Current: The carbon chamber is part of a simple electrical circuit with a direct current (DC) power source. The changing resistance of the carbon granules modulates the flow of this current. When the resistance is low, the current is high; when the resistance is high, the current is low.

* The Analog Signal: The result is an electrical current that mirrors the sound wave’s frequency and amplitude. A loud sound creates a large variation in current, while a quiet sound creates a small variation. This is an analog signal, a continuous wave that is a direct electrical representation of the original sound wave.

Fact: Edison’s carbon microphone was so effective that a version of it was still in use in many rotary dial telephones well into the late 20th century.

The Receiver: Translating Electricity Back into Sound

The electrical signal, now carrying the “voice” of the speaker, travels through the telephone line to the receiving end. The receiver, or earpiece, performs the reverse function of the transmitter, using the principles of electromagnetism.

How it Works (The Receiver):

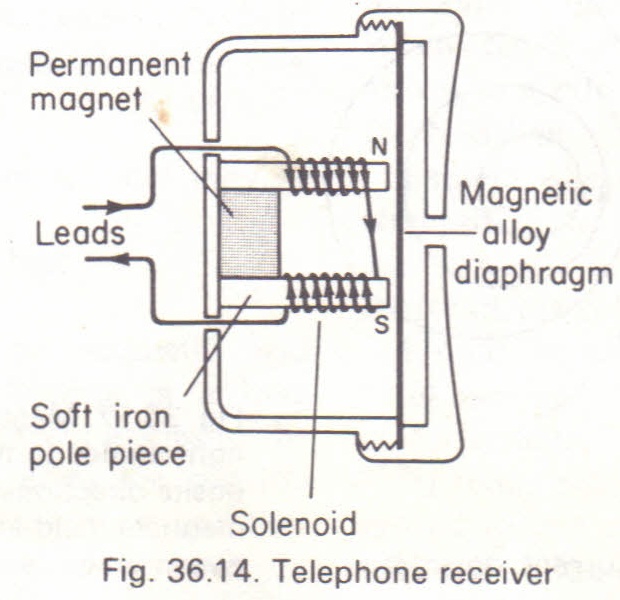

The receiver consists of a permanent magnet with a coil of wire wrapped around it. In front of this magnet is another thin, flexible diaphragm, often made of a ferrous material.

* The Electrical Signal Arrives: The incoming electrical current from the transmitter flows through the coil of wire.

* Creating a Magnetic Field: As the current flows, it creates a variable magnetic field around the coil, a phenomenon described by Faraday’s law of induction.

* Varying Magnetic Force: The strength of this magnetic field fluctuates in direct proportion to the incoming analog signal. A strong current creates a strong magnetic field, and a weak current creates a weak field.

* Vibrating the Diaphragm: This variable magnetic field attracts and repels the ferrous diaphragm. The diaphragm vibrates back and forth in perfect synchronization with the incoming current.

* Recreating Sound: These vibrations displace the air in the earpiece, recreating the original sound waves that were spoken into the transmitter. The person on the receiving end hears the speaker’s voice.

Fact: The speaker in a telephone is essentially a small, simplified version of the speakers found in stereo systems, all operating on the same principle of electromagnetism.

The Telephone Network: Connecting the Dots

A telephone is useless without a network to connect it to another. This is where the telephone exchange comes into play.

* Early Switchboards: In the beginning, connecting a call was a manual process. A caller would pick up their phone, alerting a human operator at a central switchboard. The operator would then use a physical cord to connect the caller’s line to the receiver’s line.

* Rotary Dial and Automatic Switching: The invention of the rotary dial and automatic switching systems revolutionized this process. When a user dialed a number, the rotary dial would send a series of electrical pulses. For example, dialing “5” would send five quick pulses. The central exchange’s automatic switch would “read” these pulses and mechanically connect the line to the correct destination. This eliminated the need for a human operator for most calls.

Fact: The first commercial automatic telephone exchange was installed in La Porte, Indiana, in 1892. The inventor, Almon Strowger, was an undertaker who suspected the local telephone operator was rerouting calls to her husband’s competing funeral home, inspiring him to create a switch that bypassed human intervention.

The Shift to Digital and Beyond

The traditional analog telephone system, while ingenious, had its limitations. Analog signals are susceptible to noise and degradation over long distances. The invention of digital technology changed everything.

* From Analog to Digital: Modern telephone systems, including landlines and cell phones, convert the analog voice signal into a digital signal (a stream of 1s and 0s) at the very first stage. This digital data is less susceptible to interference and can be compressed and transmitted more efficiently.

* VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol): The most recent evolution is VoIP, which converts voice signals into digital packets of data and transmits them over the internet, essentially treating a phone call like any other data transfer (like an email or a video file). This is the technology that powers services like Skype and FaceTime, and it is rapidly replacing traditional landlines.

Conclusion

The journey of the telephone from a basic vibrating diaphragm to a complex digital device is a testament to human ingenuity. While the elegant simplicity of the carbon microphone and electromagnetic receiver has largely been replaced by digital technology, the foundational principles remain the same: the clever transduction of sound into electricity and back again. The telephone’s story is a continuous evolution, but its scientific heart, the principle of converting a voice into an electrical signal and sending it across a wire, is the timeless invention that connected a world of strangers and continues to do so today.

💬 COMMENT