Light, an enigmatic force that illuminates our world and reveals the secrets of the universe, has captivated human curiosity for millennia. From ancient philosophical debates to cutting-edge quantum experiments, the study of light has driven scientific revolutions, reshaped our understanding of reality, and unlocked transformative technologies. This article delves deeply into the discovery of light, its dual nature as both wave and particle, the historical quest to measure its speed, key scientific milestones, and its profound cultural and technological impacts.

The Nature of Light: A Historical and Scientific Odyssey

The question of what light is has puzzled thinkers across cultures and eras. In ancient times, light was often imbued with spiritual significance, symbolizing knowledge, divinity, or creation. The ancient Egyptians associated light with the sun god Ra, while in Vedic traditions, light represented cosmic truth. Scientifically, however, early explanations were rudimentary. Around 500 BCE, Greek philosopher Pythagoras proposed that light consisted of particles emitted from objects, reaching the eye to enable vision. In contrast, Aristotle argued that light was a disturbance in the air, a precursor to wave-like theories. These early ideas, though speculative, set the stage for centuries of inquiry.

By the 17th century, the debate over light’s nature crystallized into two competing theories. Sir Isaac Newton, in his 1704 work *Opticks*, championed the corpuscular theory, positing that light was composed of tiny particles, or “corpuscles.” He supported this with observations of light’s straight-line propagation, reflection, and sharp shadows, which seemed inconsistent with wave behavior. Newton’s prestige lent weight to this view, but Dutch physicist Christiaan Huygens offered a counterargument in his 1678 *Treatise on Light*. Huygens proposed that light traveled as waves through a hypothetical medium called the “aether,” explaining phenomena like diffraction (the bending of light around edges) and refraction (the bending of light through materials).

The wave theory gained traction in the early 19th century through the work of Thomas Young. In his 1801 double-slit experiment, Young directed light through two narrow slits, producing an interference pattern of alternating bright and dark bands on a screen. This pattern could only be explained if light behaved as waves, with crests and troughs interfering constructively or destructively. Young’s experiment was a pivotal moment, shifting scientific consensus toward the wave model.

In the 1860s, James Clerk Maxwell delivered a monumental breakthrough by unifying electricity and magnetism into a single theory. His equations, published in *A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field* (1865), described light as an electromagnetic wave—a self-propagating oscillation of electric and magnetic fields. Maxwell calculated that these waves travel at a constant speed in a vacuum, approximately 299,792,458 meters per second, matching known estimates of light’s speed. This not only confirmed the wave theory but also revealed light as part of a broader electromagnetic spectrum, encompassing invisible radiations like infrared and ultraviolet.

The wave theory dominated until the early 20th century, when Albert Einstein’s 1905 explanation of the photoelectric effect disrupted the consensus. The photoelectric effect occurs when light ejects electrons from a metal surface, but only at specific frequencies, regardless of intensity. Einstein proposed that light consists of discrete packets of energy, called quanta or photons, each carrying energy proportional to its frequency. This particle-like behavior revived Newton’s corpuscular ideas in a new form, leading to the development of quantum mechanics.

By the 1920s, quantum theory reconciled these conflicting views through the concept of wave-particle duality. Light exhibits both wave-like properties (e.g., interference and diffraction) and particle-like properties (e.g., discrete energy transfer in the photoelectric effect), depending on the experimental context. Modern quantum electrodynamics (QED), developed by physicists like Richard Feynman, further refined this understanding, describing light as a quantum field with probabilistic behavior. Today, light’s dual nature remains a cornerstone of physics, underpinning technologies from lasers to quantum computing.

Measuring the Speed of Light: A Triumph of Ingenuity

Determining the speed of light was a centuries-long endeavor that required innovative methods and precise observations. Early attempts were speculative; for instance, in the 5th century BCE, Empedocles suggested light’s speed was finite, but no tools existed to test this. By the 17th century, advancements in astronomy and optics enabled the first quantitative measurements.

The earliest breakthrough came in 1676 from Danish astronomer Ole Rømer. While studying the moons of Jupiter, Rømer observed that the timing of their eclipses varied depending on Earth’s position in its orbit. When Earth was farther from Jupiter, the eclipses appeared delayed by up to 22 minutes; when closer, they occurred earlier. Rømer hypothesized that this delay was due to the finite time light took to travel across Earth’s orbital diameter (about 300 million kilometers). Using the best available estimate of this distance, he calculated light’s speed as approximately 220,000 kilometers per second. Though imprecise by modern standards, Rømer’s work was revolutionary, proving that light’s speed was finite and measurable.

In 1728, English astronomer James Bradley provided another estimate through stellar aberration—the apparent shift in star positions caused by Earth’s motion through space. By measuring the angle of this shift, Bradley calculated a speed of about 301,000 kilometers per second, refining Rømer’s estimate and confirming light’s immense but finite velocity.

Terrestrial measurements followed in the 19th century, overcoming the limitations of astronomical methods. In 1849, French physicist Hippolyte Fizeau conducted a groundbreaking experiment using a rotating toothed wheel. Light from a source passed through a gap in the wheel, traveled 8.6 kilometers to a mirror, and returned. By adjusting the wheel’s rotation speed, Fizeau determined when the returning light passed through the same gap or was blocked by a tooth, calculating a speed of 313,000 kilometers per second. This was the first direct measurement of light’s speed on Earth.

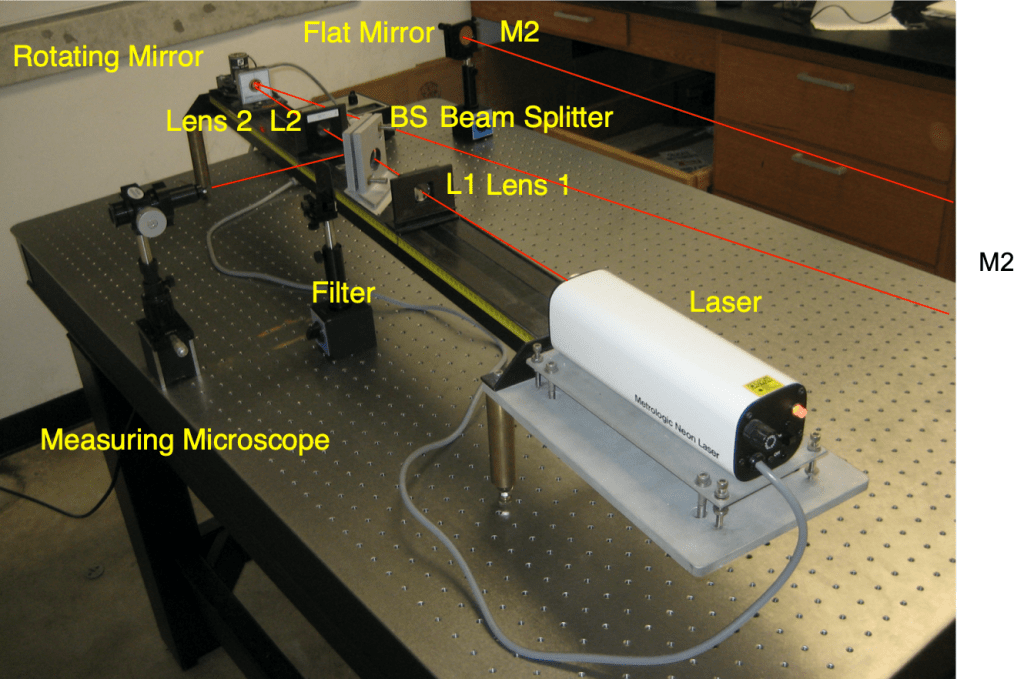

In 1850, Léon Foucault improved Fizeau’s method by replacing the toothed wheel with a rotating mirror. Light was directed to the mirror, reflected to a distant stationary mirror, and returned. The rotation of the mirror slightly displaced the returning beam, allowing Foucault to measure the time of flight. His result, 298,000 kilometers per second, was remarkably close to the modern value of 299,792,458 meters per second, established through laser-based interferometry in the 20th century.

American physicist Albert Michelson further refined these measurements in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Using a sophisticated rotating mirror setup and interferometry, Michelson achieved unprecedented precision, with his 1926 measurement of 299,796 kilometers per second differing from the modern value by mere fractions. His work earned him the 1907 Nobel Prize in Physics, cementing the speed of light as a fundamental constant.

Milestones in the Science of Light

The study of light has produced numerous scientific and technological breakthroughs, each building on the last:

1. **Refraction and Optics**: In 1621, Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snell formulated Snell’s Law, quantifying how light bends when passing from one medium to another (e.g., air to water). This laid the foundation for optics, enabling the development of lenses, telescopes, and microscopes. Galileo’s telescopes, improved by Snell’s insights, revolutionized astronomy, while Antonie van Leeuwenhoek’s microscopes opened the microscopic world.

2. **Electromagnetic Spectrum**: In 1800, William Herschel discovered infrared radiation by detecting heat beyond the visible red spectrum. In 1801, Johann Ritter identified ultraviolet radiation through its chemical effects. These discoveries expanded the concept of light to include invisible wavelengths, leading to applications in spectroscopy, medical imaging, and telecommunications.

3. **Polarization and Quantum Effects**: In the early 19th century, Étienne-Louis Malus discovered that light could be polarized, revealing its transverse wave nature. This finding influenced optical technologies like polarized sunglasses and LCD displays. In the 20th century, quantum mechanics harnessed light’s photon nature, leading to the invention of the laser (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) by Theodore Maiman in 1960. Lasers, based on Einstein’s concept of stimulated emission, are now ubiquitous in surgery, fiber optics, and data storage.

4. **Relativity and Cosmology**: Einstein’s 1905 special theory of relativity established the speed of light as a universal constant, invariant across all reference frames. This insight redefined space and time, leading to predictions like time dilation and length contraction, now critical for technologies like GPS. In cosmology, light’s properties enable measurements of cosmic distances (via redshift) and the study of phenomena like black holes and the cosmic microwave background.

5. **Quantum Technologies**: Recent advances in quantum optics have leveraged light’s quantum properties for applications like quantum cryptography and quantum computing. Photons are used to transmit secure information, while entangled photon pairs enable experiments testing the foundations of quantum mechanics.

.

Scientifically, the study of light challenged deterministic views of the universe. The wave-particle duality and quantum mechanics introduced probabilistic models, forcing scientists to grapple with uncertainty at nature’s core. These shifts influenced broader intellectual currents, from existential philosophy to modernist art, where light’s interplay of order and ambiguity inspired works like Impressionist paintings.

### Technological and Societal Impacts

The understanding of light has transformed society. Optical technologies, from eyeglasses to telescopes, expanded human perception. The discovery of the electromagnetic spectrum enabled radio, television, and the internet, connecting the globe. Lasers power modern industries, from precision manufacturing to medical procedures like LASIK. In energy, solar panels harness light to address climate challenges. In medicine, techniques like fluorescence microscopy rely on light to visualize cellular processes, advancing research and diagnostics.

### Challenges and Future Directions

Despite centuries of progress, mysteries about light persist. Questions about its behavior in extreme conditions, like near black holes, or its role in dark energy and quantum gravity, remain open. Emerging fields like nanophotonics, which manipulates light at the nanoscale, promise innovations in computing and sensing. Meanwhile, experiments with entangled photons are pushing the boundaries of quantum communication, potentially enabling unhackable networks.

Conclusion

The discovery and study of light represent a triumph of human curiosity and ingenuity. From Rømer’s astronomical observations to Maxwell’s electromagnetic theory, Einstein’s quantum insights, and modern quantum optics, light has illuminated the universe’s deepest secrets. Its dual nature as wave and particle challenges our understanding, while its constant speed anchors the laws of physics. Culturally, light symbolizes hope and knowledge; technologically, it drives progress. As we continue to explore light’s mysteries, it remains a beacon guiding humanity toward new frontiers in science and beyond.

💬 COMMENT