The atomic models we’ve been learning in school and college are indeed oversimplified and have undergone significant changes over time. You’re right; scientists have made new discoveries that challenge our existing understanding of atomic structure.

Historically, atomic models have evolved significantly.

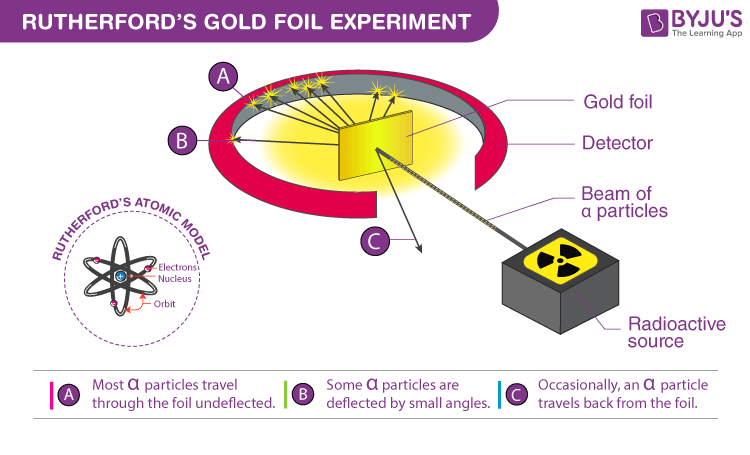

Initially, atoms were considered indivisible, but Ernest Rutherford’s 1911 gold foil experiment revealed the presence of a dense, positively charged nucleus. This led to the development of the Rutherford model, which posits that atoms consist of a nucleus surrounded by electrons. However, this model had limitations, such as not being able to fully explain atomic mass distribution and electron arrangement.

The Bohr model, introduced later, attempted to address these limitations by proposing electrons occupy specific energy levels. However, even this model has its drawbacks and has been largely superseded by quantum mechanical models that describe electron behavior in terms of probabilities rather than definite positions ¹ ².

Regarding protons, they are composed of quarks – specifically, two up quarks and one down quark. There’s no mention of a “charm quark” being part of a proton’s composition in the standard model of particle physics. Charm quarks are a type of quark that can be found in certain subatomic particles, but they’re not a component of protons ¹.

Rutherford’s atomic model had some major limitations, one of which was how the atom’s stability is maintained. According to his model, electrons orbit the nucleus in circular paths, but classical physics suggests that these electrons would emit energy and lose it, causing them to spiral into the nucleus. This instability issue was addressed by Niels Bohr in his atomic model.

The main points of Bohr’s model are:

Electron energy: Electrons don’t emit energy while revolving in specific stable orbits.

Energy emission: Energy is emitted only when electrons jump from one orbit to another.

Atomic stability: Bohr’s model helped explain the stability of atoms.

Additionally, Rutherford’s model had other limitations, such as:

Linear spectrum: Rutherford’s model couldn’t explain the linear spectrum of atoms.

Electron distribution: Rutherford’s model didn’t clarify the distribution of electrons.

Nucleus size: The nucleus is much smaller than the atom.

Despite these limitations, Rutherford’s model was a significant milestone in understanding atomic structure. Bohr’s model built upon Rutherford’s work and provided a more comprehensive explanation of atomic behavior.

Until 1936, when some physicists discovered a particle with properties similar to electrons but with a larger mass. I’m talking about 1936 when American physicist Carl Anderson performed an experiment by creating a cloud chamber with water vapor, almost frozen. He passed highly energized particles through it and detected particles that were negatively charged like electrons but had a larger mass. These particles were classified as new particles called muons.

Over the next few years, scientists discovered many more particles with properties that didn’t match protons or electrons. The number of these particles kept growing. Physicists Murray Gell-Mann and George Zweig proposed that perhaps these particles, including protons, were composed of even smaller particles called quarks. These quarks determine the quantum properties of particles, such as charge and spin. They theoretically calculated some properties of quarks, but it was still a hypothesis at that time. Scientists worked to gather experimental proof.

With advanced technology and artificial intelligence, such experiments could be performed more efficiently today. AI can help scientists analyze data and make discoveries faster. You can also leverage AI to save time by learning how to use it properly.

So, we were discussing how the concept of quarks was just a hypothesis until scientists conducted particle accelerator experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator in California from 1970 to 1976. They collided electrons with protons at high speeds to break down protons and detect their constituent particles. This led to the discovery that protons are composed of two up quarks and one down quark, held together by gluons, which mediate the strong nuclear force.

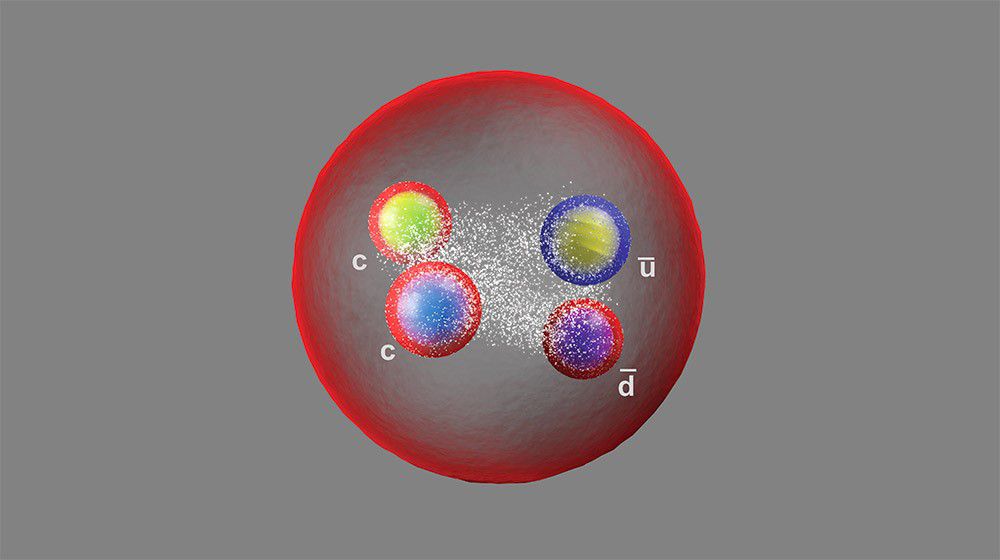

However, in one such experiment, scientists unexpectedly found a charm quark inside the proton, which was puzzling given its mass is 1.5 times that of the proton. Despite this, scientists continued to follow the theory that protons are composed of three quarks: two up quarks and one down quark.

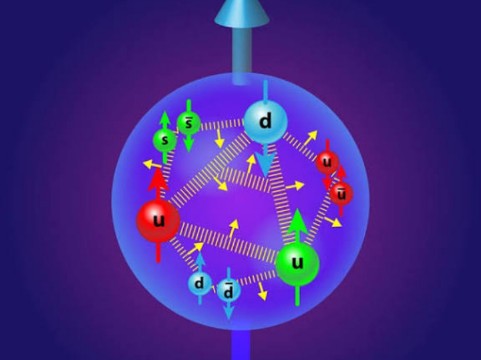

But then, quantum physics came into play, raising questions about the structure of protons. According to quantum physics, a proton’s structure is not fixed and is not just composed of three quarks. Instead, it’s a sea of quarks and antiquarks. When we capture protons, the properties like color charge and spin are conserved, and the quarks pair up with their antiquarks, leaving behind the three valence quarks.

Scientists had a theory, and they wanted to study protons in more detail. The concept of quarks was still a hypothesis, and to prove their predicted properties, scientists conducted particle accelerator experiments at the Stanford Linear Accelerator in California from 1970 to 1976. They collided electrons with protons at high speeds to break down protons and detect their constituent particles.

These experiments revealed that protons are composed of two up quarks and one down quark, held together by gluons, which mediate the strong nuclear force. However, detecting these particles was challenging due to their small size, and scientists had to repeat the experiments with different electron speeds.

In one such experiment, they unexpectedly found a charm quark inside the proton, which was puzzling given its mass is 1.5 times that of the proton. Despite this, scientists continued to follow the theory that protons are composed of three quarks: two up quarks and one down quark.

However, quantum physics raised questions about the structure of protons, suggesting that protons don’t have a fixed structure and are not just composed of three quarks. Instead, they are a sea of quarks and antiquarks. When we capture protons, the properties like color charge and spin are conserved, and the quarks pair up with their antiquarks, leaving behind the three valence quarks.

Let’s consider the circle as the wave function of the charm quark, the triangle as the wave function of the down quark, and the square as the wave function of the up quark. To understand how this process works exactly, let’s consider the circle.

First, the circle is divided into pixels, and each pixel’s information is passed to every neuron in the input layer. The input layer’s alternate neurons are connected to the next layer’s neurons through channels, each with its own weight. These weights are multiplied with the information sent from the input layer, and the output is transferred to the neurons in the hidden layer.

In the hidden layer, each neuron has a numerical value that adds to the incoming values from the input layer. This sum is then sent to an activation function, which determines whether the particular neuron in the hidden layer should be activated or not. The activated data is then transmitted to the neurons in the output layer, where the same process is repeated. This entire process is called forward propagation.

In essence, this describes a basic neural network architecture, where information flows from the input layer through the hidden layers to the output layer, with each layer processing and transforming the information through weights and activation functions.

The neuron with the highest value in the output layer gets activated and detects the output. Scientists used a similar approach with the charm quark wave function to determine if protons contain charm quarks. After analyzing data from the past 35 years, they found evidence of charm quarks in protons.

Theoretical physicist Tim Hobbs plans to build an electron-ion collider to further investigate this phenomenon, following the example of the Large Hadron Collider, which provided evidence for the Higgs boson particle. The Higgs boson particle travels through its own field, known as the Higgs field.

However, renowned scientist Stephen Hawking warned that the Higgs field could become unstable, potentially destroying the entire universe. I’ll discuss in my next blog why Stephen Hawking made this statement and how the universe could be destroyed.

💬 COMMENT