The galvanometer: a pioneering instrument in electrical measurement.

Discovered by Hans Christian Ørsted in 1820, the deflection of a magnetic compass’s needle near a wire with electric current laid the groundwork for this technology. André-Marie Ampère, who mathematically expressed Ørsted’s findings, named the instrument after Italian researcher Luigi Galvani.

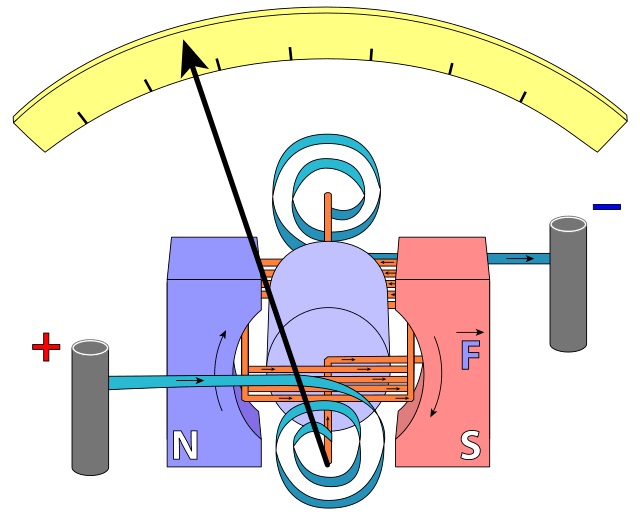

Galvanometers work by using a coil in a constant magnetic field to deflect a pointer in response to electric current. This mechanism has also been used in actuators, such as those in hard disks.

These instruments played a crucial role in scientific breakthroughs, including the development of long-range communication through submarine cables and the discovery of electrical activity in the heart and brain. Galvanometers have also been used in various analog meters, like light meters and VU meters.

The D’Arsonval/Weston type remains the primary galvanometer in use today, a testament to the innovation of early electrical researchers.

The galvanometer: a pioneering instrument in electrical measurement. Discovered by Hans Christian Ørsted in 1820, the deflection of a magnetic compass’s needle near a wire with electric current laid the groundwork for this technology. André-Marie Ampère, who mathematically expressed Ørsted’s findings, named the instrument after Italian researcher Luigi Galvani. Galvanometers work by using a coil in a constant magnetic field to deflect a pointer in response to electric current. This mechanism has also been used in actuators, such as those in hard disks. These instruments played a crucial role in scientific breakthroughs, including the development of long-range communication through submarine cables and the discovery of electrical activity in the heart and brain. Galvanometers have also been used in various analog meters, like light meters and VU meters. The D’Arsonval/Weston type remains the primary galvanometer in use today, a testament to the innovation of early electrical researchers.

Modern D’Arsonval/Weston galvanometers feature a pivoting coil, known as a spindle, within a permanent magnet’s field. A thin pointer attached to the coil traverses a calibrated scale, while a tiny torsion spring returns the coil to its zero position.

When direct current flows through the coil, it generates a magnetic field opposing the permanent magnet, causing the coil to twist and move the pointer. The pointer’s angular deflection is proportional to the current due to the uniform magnetic field.

These meters can be calibrated to measure various quantities, such as voltage and resistance, by utilizing current dividers (shunts) and voltage dividers. By placing a resistor in series with the coil, the meter can read different voltages. To measure resistance, a known voltage and adjustable resistor are used to produce full-scale deflection.

The galvanometer’s versatility makes it ideal for converting sensor outputs into readable measurements. However, parallax error can occur due to the pointer’s distance from the scale. To mitigate this, some meters incorporate a mirrored scale, allowing operators to align the pointer with its reflection and minimize error.

This design enables accurate readings and has made galvanometers a crucial tool in various applications, from electrical measurement to sensor output interpretation.

Modern D’Arsonval/Weston galvanometers feature a pivoting coil, known as a spindle, within a permanent magnet’s field. A thin pointer attached to the coil traverses a calibrated scale, while a tiny torsion spring returns the coil to its zero position.

When direct current flows through the coil, it generates a magnetic field opposing the permanent magnet, causing the coil to twist and move the pointer. The pointer’s angular deflection is proportional to the current due to the uniform magnetic field. These meters can be calibrated to measure various quantities, such as voltage and resistance, by utilizing current dividers (shunts) and voltage dividers. By placing a resistor in series with the coil, the meter can read different voltages. To measure resistance, a known voltage and adjustable resistor are used to produce full-scale deflection. The galvanometer’s versatility makes it ideal for converting sensor outputs into readable measurements. However, parallax error can occur due to the pointer’s distance from the scale. To mitigate this, some meters incorporate a mirrored scale, allowing operators to align the pointer with its reflection and minimize error. This design enables accurate readings and has made galvanometers a crucial tool in various applications, from electrical measurement to sensor output interpretation.

While galvanometer-type analog meters were once ubiquitous in electronic equipment, they’ve largely been replaced by analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) and digital panel meters (DPMs) since the 1980s. Although digital instruments offer higher precision and accuracy, analog meters still have their advantages in terms of power consumption and cost.

Today, galvanometer mechanisms are primarily used in positioning and control systems. These mechanisms come in two types: moving magnet and moving coil, and can be further classified into closed-loop and open-loop (or resonant) systems.

Some notable modern applications include:

Laser scanning systems: Mirror galvanometer systems are used for beam positioning and steering in applications like material processing, stereolithography, and laser displays.

Imaging applications: Galvanometers are used in Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy (SLO) for retinal scanning.

Bar-code scanners and printing machines: Open-loop galvanometers are used in some laser-based systems.

Military and space systems: Non-lubricated bearings in open-loop galvanometers make them suitable for high-vacuum applications.

These modern uses showcase the versatility and precision of galvanometer mechanisms in various fields.

While galvanometer-type analog meters were once ubiquitous in electronic equipment, they’ve largely been replaced by analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) and digital panel meters (DPMs) since the 1980s. Although digital instruments offer higher precision and accuracy, analog meters still have their advantages in terms of power consumption and cost. Today, galvanometer mechanisms are primarily used in positioning and control systems. These mechanisms come in two types: moving magnet and moving coil, and can be further classified into closed-loop and open-loop (or resonant) systems. Some notable modern applications include: Laser scanning systems: Mirror galvanometer systems are used for beam positioning and steering in applications like material processing, stereolithography, and laser displays. Imaging applications: Galvanometers are used in Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) and Scanning Laser Ophthalmoscopy (SLO) for retinal scanning. Bar-code scanners and printing machines: Open-loop galvanometers are used in some laser-based systems. Military and space systems: Non-lubricated bearings in open-loop galvanometers make them suitable for high-vacuum applications. These modern uses showcase the versatility and precision of galvanometer mechanisms in various fields.

In hard disk drives and CD/DVD players, moving coil galvanometer mechanisms, also known as “voice coils,” play a crucial role in controlling head positioning servos. By utilizing these lightweight and precise mechanisms, manufacturers can minimize mass and optimize access times, ensuring efficient data retrieval and storage.

Meta AI response: In hard disk drives and CD/DVD players, moving coil galvanometer mechanisms, also known as “voice coils,” play a crucial role in controlling head positioning servos. By utilizing these lightweight and precise mechanisms, manufacturers can minimize mass and optimize access times, ensuring efficient data retrieval and storage.

History

Early Beginnings

1791: Luigi Galvani, an Italian researcher, discovered the principle of the frog galvanoscope, which showed that electric current could make the legs of a dead frog jerk.1820: Hans Christian Ørsted, a Danish scientist, observed that a magnetic compass’s needle deflected when near a wire carrying electric current.

Development of Galvanometers

1820s: André-Marie Ampère, a French mathematician and physicist, gave mathematical expression to Ørsted’s discovery and named the instrument “galvanometer” in honor of Luigi Galvani.Early galvanometers were uncalibrated and used to detect small amounts of electric current.Improved versions, called ammeters, were later developed to measure current more precisely.

Evolution of Galvanometer Design

D’Arsonval/Weston type galvanometers were developed, featuring a pivoting coil in a permanent magnetic field.These galvanometers used a thin pointer attached to the coil, which traversed a calibrated scale to measure electric current.

Applications and Impact

Galvanometers played a crucial role in the development of long-range communication through submarine cables, including the first transatlantic telegraph cables.They were essential for discovering the electrical activity of the heart and brain.Galvanometers were used in various analog meters, such as light meters and VU meters, to capture sensor outputs.

Modern Developments

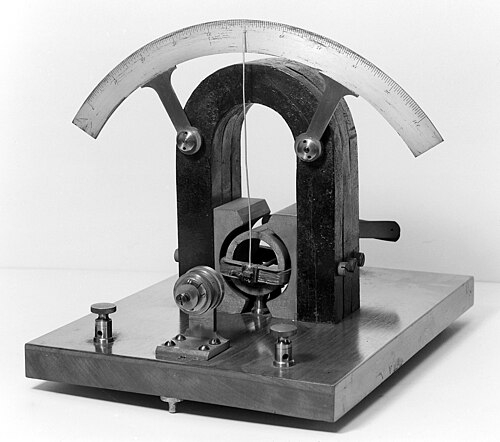

An early d’Arsonval moving coil galvanometer

An early d’Arsonval moving coil galvanometerThe advent of analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) and digital panel meters (DPMs) led to a decline in the use of galvanometer-type analog meters in some applications.However, galvanometer mechanisms continue to be used in positioning and control systems, such as laser scanning systems, hard disk drives, and CD/DVD players.

Legacy

Galvanometers have contributed significantly to our understanding of electricity and have paved the way for numerous technological advancements.Their legacy continues to influence modern applications, from precision measurement to control systems.

Early Beginnings 1791: Luigi Galvani, an Italian researcher, discovered the principle of the frog galvanoscope, which showed that electric current could make the legs of a dead frog jerk. 1820: Hans Christian Ørsted, a Danish scientist, observed that a magnetic compass’s needle deflected when near a wire carrying electric current. Development of Galvanometers 1820s: André-Marie Ampère, a French mathematician and physicist, gave mathematical expression to Ørsted’s discovery and named the instrument “galvanometer” in honor of Luigi Galvani. Early galvanometers were uncalibrated and used to detect small amounts of electric current. Improved versions, called ammeters, were later developed to measure current more precisely. Evolution of Galvanometer Design D’Arsonval/Weston type galvanometers were developed, featuring a pivoting coil in a permanent magnetic field. These galvanometers used a thin pointer attached to the coil, which traversed a calibrated scale to measure electric current. Applications and Impact Galvanometers played a crucial role in the development of long-range communication through submarine cables, including the first transatlantic telegraph cables. They were essential for discovering the electrical activity of the heart and brain. Galvanometers were used in various analog meters, such as light meters and VU meters, to capture sensor outputs. Modern Developments The advent of analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) and digital panel meters (DPMs) led to a decline in the use of galvanometer-type analog meters in some applications. However, galvanometer mechanisms continue to be used in positioning and control systems, such as laser scanning systems, hard disk drives, and CD/DVD players. Legacy Galvanometers have contributed significantly to our understanding of electricity and have paved the way for numerous technological advancements. Their legacy continues to influence modern applications, from precision measurement to control systems.

Write here