The cathode ray tube (CRT) is a fundamental piece of electronic history, a technology that dominated the world of visual display for over a century. From the bulky television sets of the past to the monitors of early computers, the CRT was the workhorse that brought images to life. Although largely replaced by modern flat-panel displays like LCD and LED, understanding the principles of the CRT is essential for appreciating the evolution of display technology and the foundational physics behind it.

A Journey into the Vacuum: What is a CRT?

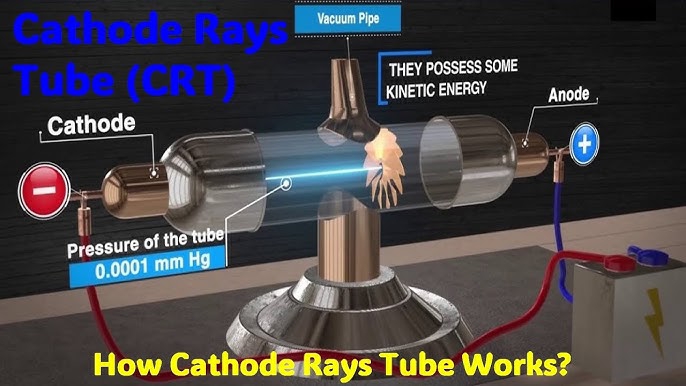

At its core, a cathode ray tube is a vacuum tube containing an electron gun that fires a stream of electrons at a phosphorescent screen. The entire device is a sealed glass envelope, evacuated to a near-perfect vacuum to prevent the electrons from colliding with air molecules. When the high-velocity electron beam strikes the inner surface of the screen, the phosphorescent material glows, producing a tiny spot of light. By controlling the intensity and position of this electron beam, a complete image can be painted on the screen.

The Inner Workings: Components of a CRT

The construction of a CRT can be broken down into several key components that work together to create an image:

* Electron Gun: This is the heart of the CRT. It’s a collection of electrodes designed to produce a focused stream of electrons. The electron gun typically consists of:

* Heater: A heated filament that warms the cathode.

* Cathode: A negatively charged metal plate coated with materials like barium and strontium oxide. When heated, the cathode undergoes thermionic emission, releasing a cloud of electrons into the vacuum.

* Control Grid: A negatively charged electrode with a small hole. It controls the number of electrons passing through, thereby regulating the brightness of the spot on the screen.

* Accelerating Anodes: A series of positively charged electrodes that accelerate the electrons to high velocities, giving them the kinetic energy needed to produce a bright glow on the screen.

* Focusing Anodes: These electrodes act like an electrostatic lens, focusing the diverging electron beam into a narrow, sharp point.

* Deflection System: Once the electron beam is focused and accelerated, it needs to be steered to a specific location on the screen. This is achieved through either electrostatic or electromagnetic deflection.

* Electrostatic Deflection: This method uses two pairs of charged metal plates. One pair (vertical deflection plates) is oriented horizontally to control the vertical movement of the beam, while the other pair (horizontal deflection plates) is oriented vertically to control horizontal movement. By applying varying voltages to these plates, the electron beam can be deflected to any point on the screen. This method was common in oscilloscopes.

* Electromagnetic Deflection: This is the most common method used in televisions and computer monitors. It utilizes a set of electromagnets called a deflection yoke, which is placed around the neck of the CRT. By changing the current in the coils, a magnetic field is generated that deflects the electron beam, sweeping it across the screen in a predetermined pattern.

* Phosphorescent Screen: The front of the CRT is the screen, or “faceplate.” The inner surface of this screen is coated with a phosphor, a material that emits light when struck by high-energy electrons. The color of the light emitted depends on the type of phosphor used. In monochrome CRTs, a single type of phosphor is used. For color CRTs, the screen is covered with a pattern of red, green, and blue phosphor dots, and three separate electron guns (one for each color) are used to excite them.

* Glass Envelope and Aquadag Coating: The entire assembly is enclosed in a thick, heavy, and fragile glass envelope that maintains the vacuum. The inner surface of the funnel-shaped part of the envelope is often coated with a graphite layer called Aquadag. This coating serves two purposes: it acts as a final accelerating anode and it absorbs stray electrons that have bounced off the screen, preventing them from interfering with the main beam.

The Working Principles: How the Magic Happens

The operation of a CRT is a fascinating dance of physics and electronics. The process begins at the electron gun, where the heated cathode releases a stream of electrons. These electrons are then modulated by the control grid to determine the brightness of the spot—a higher voltage on the grid allows more electrons to pass, resulting in a brighter spot. The accelerating anodes then propel the electron beam forward at incredible speeds.

After leaving the electron gun, the focused beam enters the deflection system. Here, a rapidly changing electric or magnetic field guides the electron beam across the screen. In a television or computer monitor, the deflection system sweeps the beam in a systematic pattern called a “raster.” The beam starts at the top-left corner of the screen and sweeps horizontally to the right, creating a single line of the image. It then “blanks” (turns off) and quickly returns to the left side, moving down slightly to start the next line. This process repeats hundreds of times per second, scanning the entire screen from top to bottom.

As the electron beam sweeps across the screen, the video signal modulates the intensity of the beam, causing the phosphor to glow with varying brightness. This creates a succession of bright and dark spots that, due to the persistence of vision, our brains interpret as a continuous image. In a color CRT, three separate electron guns fire beams at the corresponding red, green, and blue phosphor dots, and a metal plate called a “shadow mask” ensures that each beam only hits its designated color dots. The combination of these three colors in varying intensities creates the full spectrum of colors we see on the screen.

The Legacy of the CRT

The cathode ray tube was a groundbreaking invention that laid the foundation for the visual displays we use today. It was the driving force behind the golden age of television and the personal computer revolution. CRTs were known for their excellent contrast, color fidelity, and fast response times, which made them a favorite among gamers and graphic designers. Beyond consumer electronics, CRTs found applications in oscilloscopes for visualizing electrical signals, radar systems for navigation, and even in some early medical imaging devices. While the CRT’s era has passed, its contribution to the fields of electronics and visual communication remains an enduring testament to the power of scientific innovation.

Write here